January

Invisible Man – Ralph Ellison (1952)

When I was buying my course books during one semester in college, I accidentally grabbed this novel (it must have belonged to a course whose books were next to mine at the store). So ever since then, Invisible Man has been on my list. In fact, I’ve pretty much regretted not having read it since then. The novel always comes up on lists of the best or most important novels. Over this past year, it came up often as a piece of literature that white Americans should read to better understand race in this country. I guess what I’m trying to get at by mentioning all of this is that I had a lot of expectations and preconceived notions about Invisible Man before finally reading it. And I have to say that while the novel lived up to my loftiest expectations of quality, it was far different from what I expected.

To be honest, I’m surprised this novel doesn’t have an even greater reputation than it does. My expectation of Invisible Man was that it would be a late modernist work that tackled race. Something along the lines of James Baldwin or Toni Morrison. And as much as I like both of those authors, this novel is not that. The first thing I was struck by was how postmodern this book is. It is strange, funny, zany, and occasionally profane. In terms of writing, it would fit neatly beside Gravity’s Rainbow or White Noise. Honestly, I kind of think Invisible Man is even better than those novels. First, Ellison uses his postmodern style to highlight issues of race, something that most other postmodern books don’t bother with. Second, Ellison wrote this novel ten years before Pynchon and twenty years before DeLillo started tackling postmodernism. It’s surprising that as much as I heard that Invisible Man was a classic, I never heard that it was groundbreaking in terms of style.

Ironically, now that I’ve read this book, I kind of regret the timing of when I read it. To be clear, this is just a minor gripe. I am glad I read it. But it is a long, dense, sprawling book, and it came at a time in which I had a lot of things on my plate. It’s the type of book that I wish I had read in a week instead of a month. You know, now that I’m writing this, what I really want is that I had just been in whatever class was studying it. Every sentence is so beautifully written and packed with meaning. I know that it would reward further study. I suppose I’ll just have to reread it.

February

Mad Men Carousel – Matt Zoller Seitz (2015)

One of the highlights of the past year (of which there have been relatively few, thank you pandemic) has been diving into these critical companions. So far, I’ve done Seitz’ Wes Anderson Collection as well as his and Alan Sepinwall’s TV: The Book and The Sopranos Sessions. As much as I’ve admired all of those, I think that this Mad Men one is maybe the best. It strikes me that Mad Men is a show that is particularly ripe for analysis. Seitz’s writing throughout the companion book is thoughtful, provocative, and insightful. One of the series’ greatest strengths was its breadth. There are more than a dozen significant characters in each season. Seitz does a remarkable job at illustrating how the many storylines in each episode and season mirror other events in the series. I’ll miss reading these essays almost as much as watching the episodes they cover. I’d think that has to be about the highest praise you can give to a collection of criticism.

March

A People’s History of the United States – Howard Zinn (1980; 2015)

I don’t really even know where to begin. I’m glad I read this book. More than anything, I’m thankful that a book like this exists. Even as someone who considers themselves moderately woke, this book reveals an even darker history of this country than I previously realized. It’s maddening to think we live in a country with a past full of abuse, genocide, and deception of which many (if not most) citizens don’t even know about. Of course, as this book clearly lays out, that’s intentional. It’s in keeping with the primary motivation throughout this country’s history: to protect a small, elite class of citizens.

I think the most depressing part of this book was learning the history of dozens of events that I hadn’t even heard of. There are entire wars in this country’s history that I was never taught about. I couldn’t have told you about the Philippine-American war fought at the start of the 20th century. Or of our military efforts and attacks in Nicaragua, Granada, Lebanon, El Salvador, or Panama. The same goes for moments of (relative) triumph not covered in history lessons. The rise of the early 20th-century Socialist movement or the Labor movement’s success in the 1940s; Movements that indicate a potential future of this country different from the past.

I do have to be honest though and say that I am relieved to be done with this book. While incredibly informative, it has also been tremendously depressing. It’s hard to read through these 600+ pages of repeated abuse and not think this country is hopeless. And yet, I don’t think Zinn thought that redeeming this country was hopeless. Time and again, he points to the resiliency of this country’s people. Of Native Americans and Black Americans continuing to fight for justice after genocides against their people. Of the rise of the Women’s Labor movement in the late 19th century to the Women’s Rights Movement in the early 20th century to the Feminist movement in the 1960s and 1970s. Of millions of Americans (and eventually a majority of the country) who demanded an end to the Vietnam war. The most important lesson from reading this book is that we don’t have to continue on like this. However, it requires acknowledging the true history of this country before we can put an end to it.

V. – Thomas Pynchon (1961)

This marks the fourth consecutive year that I’ve read a Thomas Pynchon novel. V. like The Crying of Lot 49, Gravity’s Rainbow, and Mason & Dixon, is complicated, meandering, and incredibly difficult to assess from a standard plot perspective. Yet, like those other works, there is something hypnotic in its madness. It’s another case in which I spent the entire book trying to “figure it out,” only to reach the end feeling as confused as ever. But it’s not confusion that I am disappointed by. I don’t feel like Pynchon failed in any way in laying out his story. On the contrary, his message seems to be in the madness itself.

My (quite basic) assessment of Gravity’s Rainbow is that Pynchon was using all of this insanity (the characters, the metaphysics, the profanity) to make a general point about war. That the more you look for reasons for these questions, the more you’ll realize it’s all arbitrary. You spend most of that book following a character as he attempts to discover the correlation between his erections and the locations of V-2 bombings. Pynchon’s point is that this character’s erections are as good a reason as any for why, when, and where bombs are dropped.

In that sense, V. feels like something of a prelude to Gravity’s Rainbow (note the tie between V. and Gravity Rainbow’s central theme: V-2). We follow a group of characters who are linked in mysterious ways. Some, like Herbert Stencil, actively pursue an investigation into the mysterious identity of the titular V. Others, like Benny Profane, do all they can to avoid it and wind up in the pursuit all the same. We even have characters and stories, like Kurt Mondaugen and the history he relates of the Herero Genocide, that go on to play bigger parts in Gravity’s Rainbow.

In short, I think Pynchon’s aim here is just about the same as it is in Gravity’s Rainbow. He weaves an impossibly complicated tale in order to reflect some of the madness of the world. Trying to parse it out is difficult, if not impossible. Which is a fact he doesn’t hide either. Pynchon tells us that some of these chapters and passages have been fabricated (or Stencilized). But that doesn’t mean there isn’t any meaning in it. Quite the opposite, I think. Perhaps it’s like analyzing a dream? You can learn a lot from it, but maybe not exactly what it means in any linear, logical sense.

Breaking Bad 101 – Alan Sepinwall (2017)

Boy, it’s really going to be a drag to watch television without one of these companion books. As with The Sopranos Sessions and Mad Men Carousel, reading this book was a wonderful way to supplement my Breaking Bad binge. Sepinwall is a really sharp, insightful critic. He’s able to point out things I hadn’t paid much attention to. He even highlights a few items I had missed completely. If I had one complaint, it would be that these recaps are briefer than those in The Sopranos and Mad Men books. Alas, Breaking Bad is a different show from those series. It relies more on execution and design than thematic complexity. So maybe it’s fitting that, like the series itself, Sepinwall is direct and concise in his analysis. But really, my point is that while I am happy to read this 284-page book on Breaking Bad, I would have happily read the 600-page version.

April

Antkind – Charlie Kaufman (2020)

How do I even begin assessing this book? I guess to start with, it doesn’t work. Or at least, I don’t think it works. It devolves into a hyper-complex, dream-state, blurred reality that only Kaufman could come up with. Maybe it does work and I’m just unable to see how it comes together through this madness? To that end, I’m not sure I’ve ever read a more self-indulgent book. It’s literally 700 pages of absolute chaos. On the other hand, there are stretches of this book that are among the funniest things I’ve ever read. I think you can easily argue that over half of this book is ingenious. I flew through the first 400 pages solely on Kaufman’s writing. It’s an interesting question. Would this book be the same if it were cut in half? Undoubtedly, I think the novel could have used a more scrupulous editor. But does Kaufman reach the same highs if someone is reigning him in? Or, to get the ingenuity, do you need to give Kaufman the ability to write however much he wants to? For now, we’ll never know. Perhaps he can write a more modest novel to answer the question.

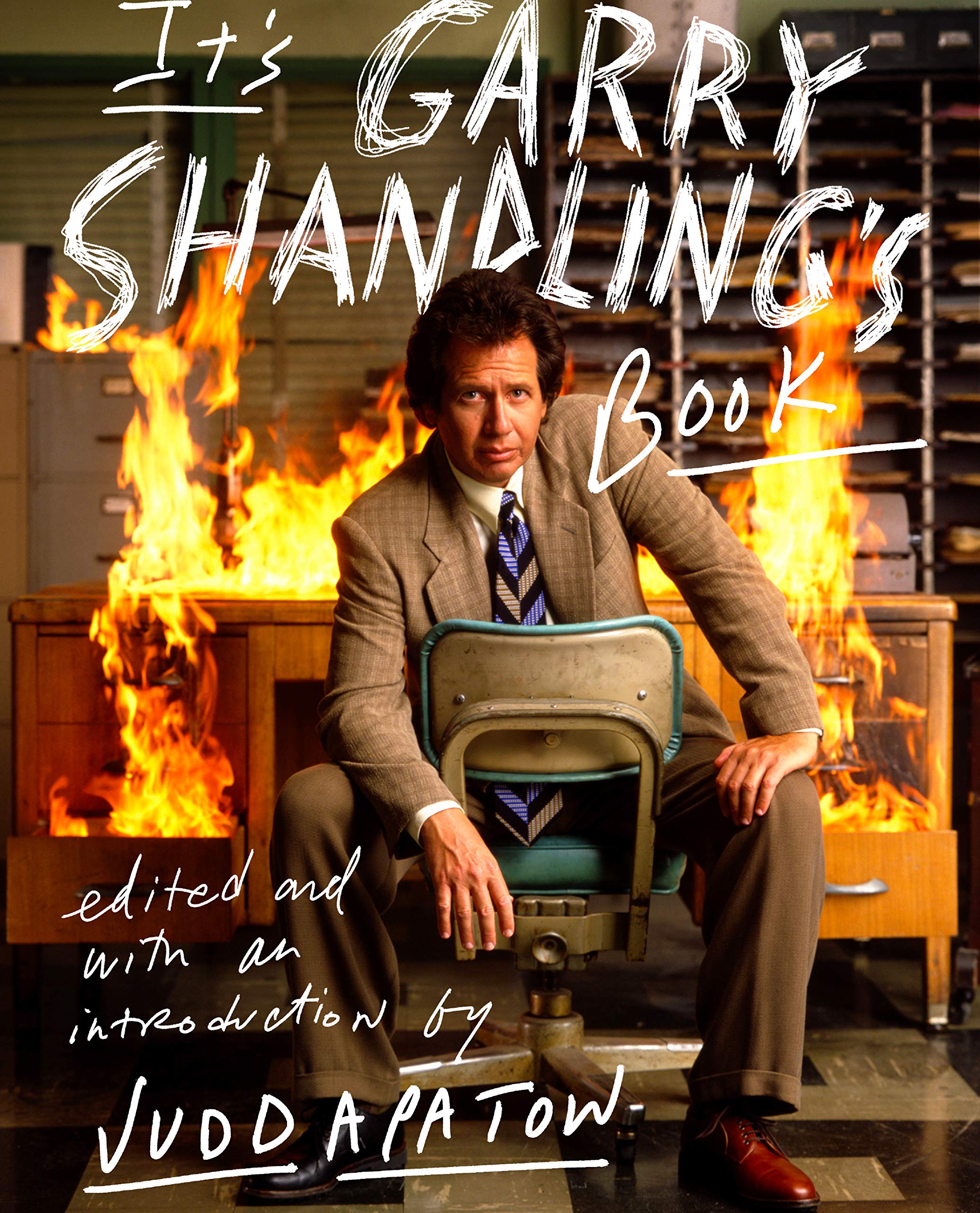

It’s Garry Shandling’s Book – Ed. Judd Apatow (2019)

I was born too late to really appreciate Garry Shandling. I honestly didn’t have much of a sense of him until Judd Apatow’s amazing documentary, The Zen Diaries of Garry Shandling. This book is more or less the companion piece to that documentary. It follows the main beats of Apatow’s film, supplementing interviews and pictures of Garry’s journals and writings. Just like the film, I was blown away. I find something incredibly fascinating in watching someone explore their life. I’ve recently been drawn to books like The Wes Anderson Collection or Mike Leigh: Interviews. I assumed it was because I was interested in these people as filmmakers. Now, I’m wondering if it has more to do with just seeing how people go about their work and even their lives in general? I think the most interesting feature of this book is that it highlights that Shandling wasn’t necessarily a perfect match for Buddhism. He worked incredibly hard at achieving self-improvement through it. Still, this book doesn’t sugarcoat that Shandling could be self-obsessive, neurotic, and demanding. The book almost suggests that those are the reasons Buddhism was so appealing to him. It’s made me want to focus on understanding myself more deeply. That’s pretty remarkable for any book.

The Wes Anderson Collection: The Grand Budapest Hotel – Matt Zoller Seitz (2015)

I think in most cases, this would be a really difficult type of book to pull off. This book is entirely centered on one movie, The Grand Budapest Hotel. It takes a special film to make that kind of investigation work. Luckily, I do think The Grand Budapest Hotel is worthy of this exploration. As such, I found this book to be quite fascinating. The scope of it is meant to cover almost every aspect of the film. There are essays, analyses, and interviews exploring the direction, music, costume, writing, performances, and inspiration behind it. I can’t imagine many other movies for which this level of breakdown would be worthwhile. For The Grand Budapest, it absolutely is.

May

There Are No Children Here – Alex Kotlowitz (1991)

Recently, I’ve been watching more documentaries than I ever have before. One of the things I’ve noticed is that I’ve become more interested in the framing of the story than the story itself. For instance, in American Factory, I far was more fascinated by the ethics behind making the film than the story of Fuyao. That’s not quite the case here. Kotlowitz does a remarkable job at capturing the lives of Lafeyette and Pharoah. I can’t imagine reading this book and caring about anything more than those two boys. Still, I think a book like this raises a lot of interesting questions. For one, Kotlowitz often writes in a way that couldn’t be 100% “true.” He writes dialogue and lines of thoughts within certain characters’ minds. All of that is obviously recreated. Likewise, Kotlowitz even admits that the characters had their unemployment cut partially because of him. The government found a piece of information in one of his articles. Still, I’m willing to give Kotlowitz the benefit of the doubt in most cases. I think what he’s able to capture in this book is true, even if some of its details have to be recaptured or recreated. I also think it’s a really illuminating book to read if you live in America. All of the events in this book take place about 3 miles from where I live.

June

The Dispossessed – Ursula K. Le Guin (1974)

I think Le Guin might be my favorite writer. I found this novel to be just as compelling as The Left Hand of Darkness. She is able to strike an almost impossible balance in her work. Her books (or at least the two I’ve read) are incredibly dense. They center on planets, races, and societies that are completely fictional. Amazingly, these societies feel wholly real and engrained. Le Guin is able to convey histories, customs, and philosophies almost effortlessly. Her novels are packed full of (quite necessary) exposition, and yet they never feel forced or overbearing. And yet, what I’ve admired most about the two novels I’ve read is their focus on humanity. The Dispossessed is a truly moving book. What I’ll remember most about it is the humanity, love, and camaraderie of its characters. I really couldn’t be more impressed. I legitimately can’t believe she accomplishes this all in under 400 pages. If I had a gripe or nitpick, I would say that The Dispossessed just sort of ends. It’s a nice ending, but not one as masterful as Left Hand of Darkness. For now, that would be the only point I could separate the two books by.

July

The Aeneid – Vergil; Translated by Shadi Bartsch (2021)

One of my reading highlights of last year was revisiting The Iliad through Caroline Alexander’s recent translation. Although I’ve spent some time studying ancient Greek and Roman texts, I had not really considered the decision-making, implicit bias, and complexity of their translations. With The Iliad, it was fascinating to compare lines between Robert Fagles’ translation and Alexander’s. Everything from the translators’ rule-set to their final word choice massively affects how the poem is understood. Maybe that’s obvious. But it was a revelation for me.

After revisiting The Iliad, I made a general plan to revisit the other ancient epics I had previously read through new translations. Fortunately, I didn’t have to look too hard for one to continue with. I quickly saw this translation of The Aeneid that was receiving rave reviews. It did not disappoint. I found every aspect of this translation, and Bartsch’s own comments prefacing it, to be massively impressive.

Let’s start with that preface. Bartsch starts by detailing the ways in which the reputation and reception of The Aeneid has been dictated by generations of white men. It inherently colors our understanding of the poem! And yet, as Bartsch points out, there is a multitude of perspectives and lenses that need to be considered. Take, for instance, how Dido’s suicide might be seen through different eyes? Or how we might think of Aeneas’s Trojans not just as noble and destined founders but ruthless conquerors of an indigenous people? On its own, the preface is a remarkable piece of criticism and introduction to the poem. Perhaps what’s even more impressive is that this preface also details Bartsch’s rules for translation. The ways in which she stays true to the line structure and length of the original Latin. It almost blows my mind to think there’s even room for her own lens on this text.

And, of course, Bartsch’s translation is wonderful. It’s a bit difficult for me to say exactly how much of that is specifically her translation vs. Vergil’s writing. Still, I was really surprised by the complexity of themes and the simplicity of the text in this poem. It is accessible and nuanced all at once. I was particularly struck by how contradictory the poem can be. Bartsch does a wonderful job at drawing attention to these inconstancies and pondering their intended purpose. All in all, I don’t have enough good things to say about this book. While I started out my journey (or odyssey, if you will) aiming to find new translations, this is one I plan to revisit. I haven’t read a book this year that I would compliment more highly.

Pride and Prejudice – Jane Austen (1813)

My first time reading Jane Austen. It won’t be my last. I found this novel to be utterly delightful. I’m amazed at how relatable, charming, and moving it is, considering it was written and set 200 years ago. Although after reading The Aeneid, 200 years shouldn’t feel like so much compared with 2000. Still, there is something about this novel, and Austen’s writing, that makes it feel almost contemporary. This is not to say that the setting or manners of it are contemporary. In fact, one of the things I particularly enjoyed was getting a taste of early 19th-century life. But the Bennets feel like a real family. Elizabeth feels like a real character. The specifics of courtship may be different, but the emotions feel the same. I keep using the word “feel” because that was my experience reading the novel. It was profoundly affecting. I don’t know if there’s any accounting for that except with Austen’s genius. Her writing is so vibrant that it’s moving to a reader who’s day to day life couldn’t be more different from her characters.

August

A Swim in a Pond in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life – George Saunders (2021)

This is one of the best books I’ve ever read. It’s the rare type of book that not only makes you strive to be a better reader and writer but a better person. I know that all sounds hyperbolic, but I truly feel that way. I really believe that reading this book has permanently improved my outlook on life. What a feat! So what’s so special about it, anyway? I guess the first point is just the subject. Russian literature has long been a blind spot of mine. Getting to read Tolstoy, Chekhov, Gogol, and Turgenev for the first time was a delight. They’re considered some of the best writers for a reason. This book is meant to approximate a class that Saunders teaches at Syracuse. It really felt that way. It reminded me of some of my favorite literature courses ever. I suppose that leads me to my next point, which is that Saunders not only introduces the reader to these stories, but he teaches them. I can’t think of another book that so thoughtfully examines how and why stories work. Or, even more broadly, why we like and need stories. Reading Saunders’ thoughts and analysis is like unlocking a bit of magic. I don’t think one could read this book without becoming a better writer and reader. Which brings me to my final point. Saunders is just the best. He’s funny and relatable and somehow not intimidating, all while quite clearly being brilliant. There’s something special in the fact that he probably could have made anything he wanted after Lincoln in the Bardo, and yet he chose to do this. To celebrate other writers and stories instead of his own.

Piranesi – Susanna Clarke (2020)

One of the most original and inventive novels I’ve read in some time. It’s astounding how vividly Clarke paints this invented world. Especially considering the conceit that it all comes from the journals of a person who doesn’t know another type of existence. The hardest thing a book like this can do is give answers. It’s always more fun to speculate on what could possibly be happening and what everything means. I think Piranesi does a damn good job at answering these questions and resolving its story. It even manages to do it in under 300 words, something quite impressive for a fantasy story.

September

Illusions: The Adventures of a Reluctant Messiah – Richard Bach (1977)

Man, I don’t know about this one. To be fair to Richard Bach, I have a pretty big aversion to these kinds of books. Really, the only one that I’ve admired is Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. I just think it’s incredibly hard to write a fictional work full of spiritual advice. Especially when, in Bach’s case, the conceit of the book is this advice is coming from a messiah. Oh well. I did enjoy the book when it played out as a work of fiction. In other words, when it dealt with its characters and a plot. I just couldn’t get down with the spiritual, self-help part of it.

A Moveable Feast – Ernest Hemingway (1964)

I can’t believe how much I liked this book. Obviously, Hemingway is a great writer. I am especially drawn to his style of prose. Formally, the book is delightful to read. Still, it’s something of a slippery slope. The bibliographical information for the book lists it as nonfiction. The characters in the book, from Hemingway’s first wife Hadley to figures like F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ezra Pound, are all real people. And yet, in notes he had written for a final chapter, Hemingway repeatedly insists that this has been a work of fiction. It’s hard to know what to make of it. Because the book deals with real people, I do think it should be taken with a grain of salt. These remembrances are all written from Hemingway’s point of view. If there’s consistency in them, it’s that he comes away looking pretty good. Still, however real or unreal the events in the book are, they’re marvelous to live through. You feel transported to 1920s Paris. I can’t believe how excited I was to have celebrity gossip on the likes of Joyce, Stein, Pound, and Fitzgerald. I think my overall takeaway is that I loved the book and will likely revisit it. However, it probably would do me some good to read other accounts of the time that are written by someone else.

October

Jitterbug Perfume – Tom Robbins (1984)

I’m not sure where I land on this one. To start with, the scope of the book’s premise is really impressive. The tagline for the novel starts, “Jitterbug Perfume is an epic. Which is to say, it begins in the forests of ancient Bohemia and doesn’t conclude until nine o’clock tonight (Paris time).” It is certainly that. My favorite part of the novel is probably in how Robbins weaves these plots together. It somehow all adds up. On the other hand, some of the writing and characterizations in this book are pretty rough. Robbins relies upon the use of sex, race, and dialects in what feels like an attempt at humor. I really thought about quitting this book early because of those elements. I’d also say the novel, especially at the end, is pretty expository. The last 50 pages are essentially a series of explanations to account for everything we’ve just read. However, I will say that I remain somewhat interested in Robbins’ other works. Particularly, Even Cowgirls Get the Blues. Perhaps I’ll just watch the movie.

This Is How You Lose the Time War – Amal El-Mohtar, Max Gladstone (2019)

I started this novel with a tiny bit of skepticism. I knew the book would be engaging and worthwhile, but I feared that some of its praise had more to do with its structural conceit rather than its substance. I’m quite pleased to say I was wrong. The form of this novel is enormously impressive. There are two principal characters. A chapter narrates the activity of one of them, let’s say Red. At the end of the chapter, Red will find a letter written by their counterpart, Blue. The next chapter consists of that letter. Then, the following chapter narrates Blue’s activity until, of course, they find a letter from Red. We then read that letter and return to Red’s activity. However, what makes this limited structure more than a clever invention is how it frames everything else in this story. These chapters only give the reader a minuscule glimpse of this world. There are hardly any specifics. And yet, almost impossibly, El-Mohtar and Gladstone are able to build an enormously imaginative narrative full of alternate realities, divine beings, and time travel. I can’t emphasize enough how impressive it is. What really sealed the novel for me was the ending. The final twist is so simple and yet perfectly done. The reader has all the clues to put it together but, amidst everything else, it can be forgotten. All in all, I have to say this novel is probably my biggest surprise of the year. I’m so glad I picked it up.

Moments of Being – Virginia Woolf (1972)

Every time I read Virginia Woolf, I come away thinking she’s the best writer I have ever encountered. There is something about her prose that is utterly captivating. It has a rhythm that I find irresistible. It turns out this quality remains true even in a posthumously-published, autobiographical book. Honestly, I enjoyed this book as much as any of her other work. She is so brilliant at capturing the significance of memories. This is a book that conveys how the past feels, not just what it was like. That’s particularly interesting when taken with the title of the book. “Moments of Being” refers to points in life that Woolf sought to capture in her work. They are moments that are at once ordinary and yet transformative. In their occurrence, they seem to illuminate a deeper understanding of one’s life or the world around them. It’s very similar to Joyce’s fiction writing which centered on epiphanies (As a side note, I would be very curious to see how these two philosophies compare and contrast with one another). One last point that I’ll make is how fortunate the world is to have something like Moments of Being. In this book, Woolf writes and examines truly devastating moments from her life. It is, if anything, privileged information. But perhaps what made Woolf such an extraordinary fiction writer was her willingness to engage with the past, no matter how painful it was.

November

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone – J.K. Rowling (1997)

What more can I say about this book? I’ve read it at least a dozen times. Having not returned to it in about a decade, I was hoping there might be something in here I had forgotten. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. Which is okay! Even ten years ago, I would mostly reread the first two books as an obligatory start to the series. The real surprises and revelations would come from the later books. Hopefully, that’ll still be the case. Even so, it’s hard to say enough about what Sorcerer’s Stone manages to accomplish. It seamlessly introduces the reader to the greatest mythical world and story ever created. Its plot may be simple, but it’s highly effective. What impressed me most this time was how accessible the world feels from the start. There isn’t a ton of description or expository information in this novel. Or, I should say, more than what feels natural in a children’s book. And yet, all of these places and people feel effortlessly real. I honestly don’t know how Rowling was able to do it. I guess I’m just thankful that she was.

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets – J.K. Rowling (1998)

Chamber of Secrets has always been my least favorite Harry Potter book. Not to say that’s such a terrible distinction. I think most readers would agree that the first two installments are clearly the weakest in the series. For me, the choice between Chamber of Secrets and Sorcerer’s Stone mostly came down to which book didn’t feature a giant snake. And yet, to my surprise, I think I have to change my opinion. I really enjoyed Chamber of Secrets this time. I was especially impressed by how brilliantly the story unfolds. Rowling sets up an extraordinarily clever mystery full of clues and misdirections. On top of the chamber, there are revelations about Hagrid, Moaning Myrtle, Tom Riddle, Ginny, Dobby, and the Malfoys here. Even knowing the outcome, it was hard for me to put the book down. In the bigger picture, it probably cannot be overstated how important this book was for the series. There are dozens of great fantasy novels. There are far fewer great fantasy series. Getting book two right was crucial and I think Rowling absolutely nailed it. If I had a complaint, it would just be with the giant snake.

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban – J.K. Rowling (1999)

Man, oh man. This book really does take a massive leap from the first two. I wish I could put my finger on what makes Azkaban so special. I suppose a few things come to mind. First, Sirius Black and Remus Lupin are two of the best characters in the series. I love reading about their adventures with Harry’s dad at Hogwarts. Likewise, these characters allow Rowling to give the reader a first glimpse into the time during Voldemort’s rise. We can begin to understand the organization behind him as well as the initial resistance. Second, the final 100 pages of the book are the finest in the series to date. Sure, it is mostly exposition, but Rowling is able to reveal layers upon layers of secrets and mysteries. We learn about the Marauders and their secret identities. We learn about the time-turner. Most importantly, we learn the truth about Sirius Black and what happened the night Harry’s parents died. I guess what I’m finding is that aside from being a perfect story, Azkaban is also the book in which the scope of the series gets so much bigger. No wonder it was my favorite for so long.

December

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire – J.K. Rowling (2000)

I should clarify that from this point, I will be reviewing these books not only on their individual merits but within the scope of the entire series. As I mentioned in my Azkaban entry, this series takes a massive leap forward after the first two novels. From that point on, I genuinely believe that each of these novels deserves consideration as the best book in the series and, by extension, one of the greatest books of all time. Having said that, Goblet of Fire has always been the entry that underwhelms me most compared to its general reception. For the most part, that sentiment held true during this reread. There are a few things in this novel, compared with the rest of the series, that I believe work against it. The first is that Goblet of Fire contains one of the more convoluted plots of the series. To buy in, you must accept that Barty Crouch (Junnnnior!) is able to mimic Mad-Eye Moody so closely that he takes his place as the Defense Against the Dark Arts teacher for an entire year while working to ensure that Harry wins the Tri-Wizard Tournament. I love this book and series enough that I can get past it, but it’s a big ask! The second piece that I bump up against is that this book slightly departs from the standard Hogwarts Year. So instead of the usual hallmarks (Quidditch, Halloween, Christmas, etc.), we have the Tri-Wizard Tournament. However, there is one enormous counterweight against these points. That is the return of Voldemort in what is easily the best chapter of the series to date. Having read this novel a dozen times, I still was astounded by this ending. It is one of the most thrilling, moving, and beautiful passages of any book I have read.

Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix – J.K. Rowling (2003)

The longest and most divisive book in the series. I’ve always been someone who’s liked this book more than others. Still, I can certainly see how it can be a slog. First, as I stated above, it is the longest entry in the series. There are parts of the novel that just drag. In retrospect, it is kind of amazing that this is longer than both Half-Blood Prince and Deathly Hallows. For as much as I like Order of the Phoenix, those last two novels have more significant plot points to hit. Second, this book is bleak. Overall, Deathly Hallows is a darker novel, but at least it has a happy ending. Order, instead, ends with Harry making a terrible mistake that costs his godfather his life. Finally, and to that point, Rowling makes Harry a challenging protagonist in this book. He’s angry, frustrated, and often a bit childish. To put it bluntly, he’s a tough hang. So why do I still like this book so much? While all of the points above make Order of the Phoenix a challenging read, they also add so much to the overall story. It really means something that someone like Harry (or even Dumbledore!) is capable of grave missteps. It makes him human. The end of Goblet of Fire is where the series turns. With Voldemort’s return, Harry is forced to leave his childhood behind. Order of the Phoenix cements that change. It is long, bleak, and often challenging, but it is also incredibly true to its characters and this world. To me, it’s the foundation for how the series is able to close so masterfully.

One thought on “2021 Reading Log”