January

The Neapolitan Novels – Elena Ferrante: My Brilliant Friend (2012), The Story of a New Name (2013), Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay (2014), The Story of the Lost Child (2015)):

An absolutely incredible series. The world of the story is so intricately detailed. I felt so connected to it. Ferrante writes more viscerally than any writer I’ve read. Reading the last 100 pages of the third novel is as furious as I’ve ever been from a story. A truly amazing four novels that I will definitely revisit at some point.

The Days of Abandonment – Elena Ferrante (2002)

Another stunning book by Ferrante. But unlike her Neapolitan Novels, I will surely never read this again. The narrator’s anguish is so painful to read. You feel completely trapped by her misery. I’m especially glad I read this after reading her other work. This novel focuses so squarely on anger, paranoia, and despair. I was glad to know she is more than capable of eliciting other emotions when she wants to.

February

Crossing to Safety – Wallace Stegner (1987)

A beautiful novel. It’s one of the most earnest books I’ve ever read. The characters, and especially Larry, are so full of hope, optimism, and belief in the world. It’s infectious. Of course, the novel takes a turn. The ending is devastating. But I don’t believe the book was ever cynical. If anything its ending only reinforces the ties of friendship and love.

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance – Robert Pirsig (1974)

I anticipated this book being difficult. The first half, at least, is not. It’s incredibly engaging. Both the story of the road trip and the narrator’s reflections on quality feel so urgent. It’s hard to put down. As the story reaches a climax, the philosophy gets more advanced. I definitely started to lose the thread of Pirsig’s thoughts in the last 100 pages. However, I do believe I understood most of his argument.

April

Dune – Frank Herbert (1965)

Most of Dune underwhelmed me. That was surprising. I anticipated really loving it given that it comes up frequently alongside some of my favorite books: A Song of Ice and Fire, The Lord of the Rings, and even Harry Potter. Granted, these are all fantasy novels and series, and Dune is pretty strictly science-fiction. My problems with the book, however, weren’t with conventions of the genre but the storytelling.

Dune‘s scope is enormously broad. I think A Song of Ice and Fire is really the only comparison, and still, that may not be enough. Herbert touches not just on dozens of key characters, but whole planets, races, and the political and religious framework that ties it all together. Yet, as all this is happening, we’re following Paul’s journey from a Duke’s son to a Messiah. I didn’t feel like I spent enough time with any of the characters to form emotional bonds. This especially happens with the antagonists, the Harkonens and Feyd-Rauta, who sporadically appear and then must somehow rise up to be the novel’s villains.

The scope of Dune is incredible. For that reason, I believe the upcoming film could likely be amazing. I just wish the storytelling had been less broad.

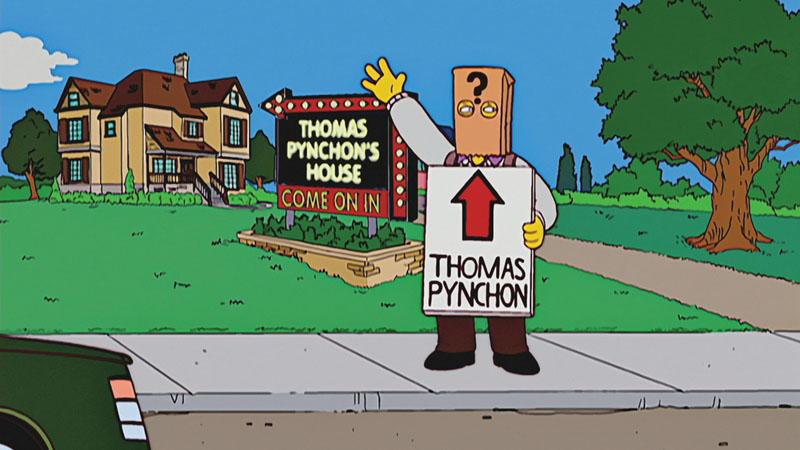

Gravity’s Rainbow – Thomas Pynchon (1973)

(Along with A Gravity’s Rainbow Companion – Steven Weisenburger (1998) and Gravity’s Rainbow, Domination, and Freedom – Luc Herman and Steven Weisenburger (2013))

I spent over a year with GR. I read the first 2/3rds in about 5 months, taking meticulous notes and going line by line in the companion. About 7 or 8 months later, I read the final 1/3 in about a month, this time mostly skipping the companion book.

All of that being said, I found GR to be incredible. It’s hilarious, despicable, irreverent, and moving all at once. Everything in the book is inextricably linked, centering upon themes of determinism, capitalism, and war. I’ve found the Domination and Freedom book to make some really good points on the philosophy and psychology Pynchon is referencing in his book.

GR is the type of book that the more you put into it the more you get out. This isn’t surprising to me given its scope and size. I was nervous that this would be limited to an intellectual reward. After all, this is the postmodern novel. Yet, even through all of the hi-jinx and horror, I think that the novel is ultimately emotionally rewarding. It’s extremely dark, but strangely moving nonetheless.

May

Suttree – Cormac McCarthy (1979)

I had read the first 100 pages or so about a year ago for Bryce’s book club. While I found some parts amusing, I was ultimately bogged down by its lengthy descriptions and meditations on the filth (real and metaphorical) of Knoxville, TN. The second time reading, I pushed through. What’s surprising is that the second time through, these meditations are what I found most rewarding. I think it was ultimately a matter of not seeing the forest for the trees. The novel is comprised of stories and adventures involving Suttree. But ultimately, these stories aren’t really connected in a major way. What’s more, there’s not really a major plot they build toward. Instead, these vignettes could almost function as a collection of shorts that give us an impression of Suttree, the town, his life, and the people around him. At the beginning, I felt unsettled each time McCarthy would leave one story for another. But then, I learned to trust the novel and appreciate each new story for where it was going. The best example is Suttee’s time with the Oyster farming family. At first, I was so disappointed. I didn’t like the characters. I was displeased to have physically left the setting of Knoxville. By the end, it was my favorite part of the book. A biblically dark rumination on work, sacrifice, life, and death. I’m so glad I pushed through. It wasn’t an easy read, but it was rewarding.

July

What I Talk About When I Talk About Running – Haruki Murakami (2007)

I flew through this book. It’s definitely designed to read that way. I found the first 150 pages to be incredibly compelling. Murakami’s prose is so simple and vivid. It’s a fascinating window into his mind. The crux is that this clear, no-frills writing style really relies on the specific mediations to be worthwhile. The majority of the them are. I was particularly fascinated by Murakami’s recollections of starting out as a writer, and then as a runner. I was intrigued by his approach to training, and specifically how his relationship with running has evolved as his body starts to age. I found the last section of the book to be less interesting. And in this case, his clear cut approach doesn’t allow for any stylistic flourishes to elevate it. I was not particularly interested, for example, in hyper-specific descriptions of his swim lessons. Still, I haven’t spent much time reading memoirs. I can see from this one that there’s real value in getting a glimpse inside someone else’s mind.

The Hundred Secret Senses – Amy Tan (1995)

This was a real struggle for me. So much so that I finished a couple of other books while reading this one. Overall, I think it’s squarely mediocre. The biggest issue with I had with the book was that the characters are unlikable. The plot centers on many fantastical elements happening within the framework of a normal universe. I’m guessing it’d be classified as Magical Realism, a genre I have little familiarity with. Moreover, I’m guessing for the genre to work, you need to be on board with the characters’ journey through these fantastical elements. And in this book, I really could not get on board with Olivia. For most of the novel, I felt like the story was completely convoluted. It does all come together at the end in a pretty impressive way. I’d be interested to see if Tan’s other work lives up to the hype. But for now, I will be taking a break from her.

Seven Plays – Sam Shepard: True West (1980), Buried Child (1979), Curse of the Starving Class (1976), The Tooth of the Crime (1972), La Turista (1967), Tongues (1978), Savage / Love (1981):

My first entry into Sam Shepard! Really my introduction into 20th Century Theater. Aside from Shakespeare, and the ancient Greek and Romans, I really haven’t read much theater at all. It’s clear in these plays that language is the dominant force. It feels very much in line with Quentin Tarantino. The story, drama, and themes are all weighty, but it’s the words that are supposed to punch you in the mouth. True West, Buried Child, and Curse of the Starving Class were my favorites. They are also apparently part of a thematic trilogy. It makes sense. Each of these plays is structured in incredibly similar ways. Each centers on a fractured family dynamic. Each play features a member or members of the family attempting to remake themselves or have an awakening. Each also deals with the actual bonds of the family. Many of these members are distant or unrecognizable to each other. Aside from these dynamics, Shepard zeroes in on economic disparity and inherited hardship. Out of the collection, these three plays were also the most straightforward. They aren’t necessarily easy or what I would expect to be mainstream, but they are rooted in conflict and have a clear resolution. The Tooth of the Crime is wild. It’s a surrealistic rock and roll musical. I imagine it has to be seen to be fully understood. From reading it, my impression is that Shepard is trying to create his own mythological world in the likeness of so many rock and roll songs. Jungleland by Springsteen comes to mind. My least favorite play in the collection was La Turista. It is a bizarre, surreal, two-act, meta-commentary on…I’m not sure. It uses really provocative language and racist characters. It deals with Western expansion, privilege, and colonialism. Finally, there are the plays Savage/Love and Tongues. While I understand they’re meant to be performed and accompanied by music, on paper they are poems. So while I didn’t get the full scope of what these plays were meant to accomplish, I did feel like I could appreciate their language to some extent.

Ordinary Grace – William Kent Krueger (2013)

This book was so good. I haven’t had such a compulsion to keep reading a story in a long time. I literally couldn’t put the book down during the middle 100 pages. It’s a strange and powerful amalgamation of so many stories I like. On the one hand, it’s a deeply meditative book on innocence, loss, and death. It touches on a broad swath of issues including trauma from the war, racism, prejudice, and colonization. Yet, there is a crime story set on top of this world. One that moves pretty fast too. The second half of the book is in many ways a pretty straightforward mystery. At times during the last stretch, I wished the book would slow down and remain a little more meditative. In some ways, I think the novel could have been even more powerful if the mystery wasn’t solved. Along similar lines, I wish the death toll didn’t get so outrageously high. The outing and death of Karl Brandt started to border on melodrama. That being said, I liked the ending of the book. It was powerful, satisfactory, and moving. I think what really carried the novel was the strength of its characters. They were all deeply rooted. You couldn’t help but feel for and admire them amidst all this tragedy. The standouts are Jake and the father. The father felt to me like Atticus Finch in Minister’s clothes. Still, he fit into this story and provided a moral compass. Likewise, Jake’s arc was incredibly moving. He served as a pillar of innocence and goodness. I was really moved when he’s able to overcome his speech impediment. In any other story, I’d probably be dubious. But amidst all the heartbreak, this one felt just. Overall, this book just hit me in all the right spots. I think it probably has some flaws. I’m still not sure if it’s a religious / Christian book. I think the portrayal of women in the book is a little cliché. Still, it has me thinking about the type of stories I’m drawn toward. Ones that are thoughtful and deep and structured on its characters.

August

Calypso – David Sedaris (2018)

Although I’ve seen David Sedaris before, this was my first time reading him. I found this collection of stories to be so profoundly human. Sedaris has a real talent at telling colorful, insane, outlandish stories. So much of this book, in fact, is focused on his talent in telling stories, as opposed to the stories themselves. In “Sorry,” Sedaris compares his family to his in-laws specifically in the way they tell and listen to stories. How exaggeration, suspension of belief, and attachment to the narrator are all practiced in his family. Meanwhile, Hugh’s family interjects to dispute details and find compassion with the other side. In “Why Aren’t You Laughing,” Sedaris details his family’s relationship with their mother and her alcoholism. Specifically, he recalls how she actually groomed all their kids in telling stories: what details to focus on and what parts to leave out. The title is a commentary on this very feat. It’s about Sedaris letting his partner read manuscripts and his focus on the feedback. It calls attention to the way he balances sadness and comedy. The balance of this collection is probably 65% comedy, 35% tragedy. It really makes the somber moments so poignant. The greatest examples are Sedaris relaying stories about his estranged Sister who committed suicide. Likewise, Sedaris details his difficult relationship with his father. I really loved this book. It made me feel so connected to Sedaris and his family. I will definitely be reading more.

To the Lighthouse – Virginia Woolf (1927)

I had read To the Lighthouse at some point in college, but not close enough for it to stick. It is a masterpiece. What Woolf is doing is dazzlingly impressive. Word for word, she could be the best prose writer I’ve ever read. This novel is a clinic in stream of consciousness writing. It moves effortlessly between different characters’ thoughts within the same paragraphs and sometimes even within the same sentences. Lily Briscoe will look at Mrs. Ramsay as she paints, which transitions to Mrs. Ramsay’s thoughts about how Charles Tansley disappointed her son, which moves into a trip she took into town with Charles Tansley, which will transition back into her looking out at the field and seeing Lily Briscoe painting her. The novel’s major accomplishment is this presentation of multiple perspectives. It never feels like a gimmick or purely stylistic exploration. It’s so interwoven, it feels like the only way you could tell this story is through this style of prose. I am really just in awe of Woolf’s writing. I will definitely be exploring her other work.

September

Pet Sematary -Stephen King (1983)

Shamefully, this was my first Stephen King novel. I had previously read Faithful, his email correspondences during the 2004 Red Sox season, as well as Four Past Midnight, a collection of (mediocre) short stories. I had wondered what the trick was. Why do people love Pet Sematary so much? I can understand the buzz around It or The Shining. The premise of those books is terrifying. But Pet Semetary? It’s always seemed so silly to me. And while the movie is laughably bad, I figured it could be due to production and execution issues as much as the story itself. Here’s the thing: I think Pet Sematary is extraordinarily silly. It is so steeped in horror and magic, it’s just hard for me to take it seriously. That being said, I think Pet Sematary is also a pretty good book. Stephen King is a master storyteller. It’s really unbelievable. I’ve never felt so compelled to keep reading a story that I didn’t especially care for. I think the power of this book is almost solely in its telling. What’s more, King probably knows that. Throughout the first 2/3rds of the book, he spoils everything. Not even just foreshadows but straight up announces each death that will occur. On its face, it’s impressive King is good enough to do this and trust that his readers will keep going. Beyond that, it sets up the final act of the book. The part of that book that is genuinely terrifying. Through the novel, you’ve been trained by King to feel the pull of the story and of the sematary. By the end, when for the first time he isn’t telling you what will happen, you still know what will happen. It’s inevitable! And like the characters, you have to stand by and watch it happen. It’s incredible. He’s the best for a reason.

The Haunting of Hill House – Shirley Jackson (1959)

It was funny reading this after Pet Semetary because this book feels like a prototype for so many King stories. Particularly, The Shining. I thought Hill House was incredible. It’s short but perfect story. I loved how every aspect of it was carefully layered. We meet our gang: Eleanor, Theo, Luke, and Dr. Montague and realize that they reflect the history of this house. Luke, for instance, is a petty thief. We learn that his ancestors, squabbled over inheritances in the house as they appeared to go missing. Likewise, Eleanor arrives having just lost her mother. The twins who first inhabited the house also lost their mother. The novel is carried by the characters. They’re funny and compelling. You feel a sense of camaraderie living in the house with them. The relationship between them sours as the novel moves along. But at this point, the disturbances more than carry the book. I particularly liked when Arthur and Mrs. Montague come to the house. They’re perfectly hatable. The real hallmark of Hill House though is the ending. As I mentioned before, the story really works because of how carefully layered it is. It’s made even more powerful as we learn the disturbances are being caused by Eleanor. Whether it’s possession by the house or just a psychological break is left up to the reader. But it allows the story to completely resolve itself in surprising fashion. I was really impressed.

The Bluest Eye – Toni Morrison (1970)

Early in college, I read Beloved. While I found it challenging and impressive, more than anything I was deeply unsettled. It’s a provocative, difficult novel. It’s supposed to be confrontational and upsetting. I’ve read some other books that are meant to provoke. Lolita or A Clockwork Orange come to mind. But in both of these cases, the narrators are charming. The prose is fun and disarming. Confronting that is difficult, but the act of reading is made easy.

The Bluest Eye falls somewhere between these two modes. For a while, it is certainly upsetting, but not an unpleasant read. The care and detail Morrison puts into each of these characters is disarming. You feel their pains and desires. You find delight in their pleasures. More than anything, I think the amount of empathy you feel is overwhelming. It’s hard to be put off by a book that makes you feel so deeply for its characters.

This structure is part of a larger design. The Bluest Eye is undoubtedly meant to be upsetting and confrontational. Morrison builds up these different characters to show how they all contribute to the horrors left for the end of the novel. Like each of the characters in the book, Morrison makes you, the reader, feel complicit in this outcome.

I feel lucky to have read so many great books this year. That’s the wonderful aspect of reading classics. Most of them are bound to hold up. The Bluest Eye may be the best one I’ve read. If not the best, certainly the most impactful. From my own sheltering, Beloved was too painful for me to fully grasp the power and message of Morrison’s writing. I feel like this novel unlocked it. In a forward, Morrison laments her lack of ability in changing writing styles throughout the book. With respect to her, I have to disagree. I thought the way she is able to weave in and out of styles with different characters is astounding. By the time they come together at the tragic end of the novel, it’s all the more powerful.

Little Women – Louisa May Alcott (1868)

In the words of my brother Max, “What a delightful book!” It’s a remarkable document of life. It’s insane how well the humanity shines through considering it was published in 1868, 151 years ago. I mean, the first part of the novel is written and set during the Civil War. I know there’s a lot of classic literature that holds up. The Iliad is believed to have existed before written literature. Still, even with something like The Great Gatsby or In Search of Lost Time, they feel tied to a period in time. I think those novels are so focused on documenting their reality that they can’t help but feel dated. It’s not to knock either one of those books. They’re both profound works of literature. My point is that Little Women feels true to life in a way that few works of art do, even if it is 150 years old.

I think the best parts of Little Women are all in Part 1. The life that exists between our 6 main characters is incredibly charming. You grow to not just understand, but to love Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy, Mrs. March, and Laurie. It’s made all the more impressive considering that most of the trials are fairly minimal. It usually has to do with chores and manners. Alcott finds life in everyday moments. There are quite a few big moments in Part 1 too. Beth and Mr. March’s mutual illnesses are harrowing. Meg’s courtship and engagement is a big moment as well. I’m still drawn to the smaller bits though. The dinner party in which Jo and Laurie meet is one of the most charming moments I’ve ever read. I’m smiling just thinking about it. Another highlight is Beth’s relationship with Mr. Laurence.

Where Part 1 is almost timeless for me, Part 2 has a few moments that are dated. First off, I think it hurts the novel that the sisters are apart. Nobody suffers for it more than Meg. In Part 1 she shines as a character for her reserved leadership as the oldest sibling. You feel for her as she goes through many of life’s trials first. The ball in which she dresses up or her courtship are examples. In Part 2, these moments don’t work as well. Her trials as a mother feel less meaningful without her sisters there to learn from and support her. I think the book shows its age here too. Many of the ideas of family and young marriage feel especially dated. Part 2 also suffers in that it removes Beth. Aside from Jo, she’s the best character in Part 1. In Part 2, she doesn’t have any point of view chapters. She exists as a model of faith and suffering for her family. It’s less impactful when she dies because we don’t see her truly live in Part 2.

The Jo, Amy, and Laurence storylines are the highlights of the second part. I do feel aversion to how it turns out, but I think that’s a sign that it works. It’s eliciting such a strong reaction, even if it’s disagreement. Alcott still does a great job of resolving everything well. You feel surprised and delighted when Mr. Baher shows up to court Jo. Still, it’s hard for me not to think of Jo and Laurie as a perfect couple. It feels off for Laurie to be rejected and then end up with Amy.

I’m incredibly glad I decided to read Little Women. I wish I could bottle up the experience of reading the first 300 or so pages. I’m excited for the movie even if it’s supposed to focus on Part 2. I think it may actually work better for me to re-contextualize some of the parts I didn’t like. I hope Gerwig can capture the many aspects of this novel that are timeless. It’d be a bonus if she can update the few parts that aren’t.

October

The Elegance of the Hedgehog – Muriel Barbery (2006)

To start off with, I think this was one of the worst books I could have followed up Little Women with. Little Women is the most earnest, optimistic, and life-affirming piece of literature I have probably ever read. It is wholesome. The Elegance of the Hedgehog starts out being one of the most cynical and pretentious pieces of literature I have read. For about the first 200 pages I really hated it. Why? The novel is told through the perspectives of two characters who I really couldn’t stand. You have Renée, the concierge. She has lived a life hiding her intelligence, working as a concierge at a bourgeoise apartment building. She is unbearable. Despite the fact that she feels the world has done her a great injustice (which it has), she is the worst person in the apartment complex. She sits and picks apart her tenants. All because they have money but not the same intelligence as she. When she reads through Colombe’s thesis, she laments the fact that this is what the rich, well-educated, waste their privilege and resources on. All the while, she has been hyper-intelligent and is literally hiding it from the world. She doesn’t do anything except pick her tenants apart. We also get the perspective of Paloma. A precocious 12-year-old who has decided that the world is so terrible and unworthy of her intelligence and perception, that she’s going to set fire to the apartment and kill herself. I find her more bearable than Renée, but just in the fact that at least she is young so she has an excuse to be so stupidly arrogant. That’s where I was, 200 pages into the book. I was sure this was destined to be a novel that I hated. While I don’t think it’s particularly good, the novel proceeds from there at a best-case scenario for me. Renée and Paloma meet Monsieur Ozu who is able to unlock the intelligence from both characters. The thesis of the book becomes not a rejection of the unintellectual elite, but that art, culture, and intelligence need to be shared. The novel rejects and repositions both Renée and Paloma’s outlooks on life. So thankfully, I really enjoyed the last 120 pages of the novel. There were some parts that were charming and really funny. I’m not sure they really do enough for me. You still have to sit through 200 pages of pretension to get there.

The Secret Life of Bees – Sue Monk Kidd (2001)

I flew through the first half of this novel. Lily, the narrator, is so engaging right from the start. I think the prose was refreshingly breezy after Elegance of the Hedgehog. You probably can’t get much farther apart than a French philosophical translation and a rural South Carolina dialogue. The novel is fine but didn’t completely hold together for me. It roots itself in one issue which is Lily’s guilt and sorrow over her dead mother. While I think the events of the novel provide some catharsis and shed light on grief, I’m not sure it was enough to earn the whole novel for me. In a way, it was similar to The Hundred Secret Senses. I think every theme and issue each novel tackles is worthwhile. But it feels a little too neatly put together to pay off in a big way. In other words, I don’t think the major themes each novel tries to convey are totally earned. This novel also had something of a Green Book issue. It’s set in 1964 South Carolina at a black home. Yet our protagonist is white. The novel is decidedly more interested in Lily’s internal struggles than any of the other characters or the Civil Rights Movement. I don’t think anything in the book is problematic per se. It just feels like it’s telling a less essential story.

The Art Of Hearing Heartbeats – Jan-Philipp Sendker (2002)

I think the beginning of this novel is really rough. I don’t know if I’ve seen an exposition download quite like this one. The story opens with our avatar, Julie, arriving in Burma and hearing paragraphs upon paragraphs of information we need to know. What is odd is that this becomes the framing device for the rest of the novel. The rest of the novel is U-ba telling Julie the story of her father. But we don’t know this yet. At this point of the novel, we think the story will be Julie’s quest to find her father. I really don’t know why they framed it this way. Obviously, the book is trying to set up this great mystery. How could Tin Win vanish and abandon his family? What would justify this action? For the rest of the book we get a fairly compelling case. I think the best parts of this novel are good. It’s magical and so, so romantic. The novel doesn’t have any issue setting up how much Tin and Mi Mi loved one another. So this solves the initial problem. But, it really just creates a bigger one. I don’t buy for one second that Tin Win would have left Mi Mi. In the story, it’s chalked up to the conservative nature of Burmese society. That seems extraordinarily weak to me. What’s even more perplexing is how utterly cartoonish the villain behind their separation is. His whole goal is to cure Tin Win’s blindness and thus appeal to the gods. His task is to help a distraught and suffering family member. So he does this and chooses to provide Tin Win the best education he can buy. Yet he also reads Tin Win’s and Mi Mi’s correspondences and hides them from each other? He works tirelessly to keep them apart. And why? Because he thinks love is foolish? It’s total bullshit. So does the novel work? On the one hand we get a very endearing and compelling love story between Tin Win and Mi Mi. On the other hand, Sendker chooses to frame it through the less of Tin Win’s daughter and to double down on it being a tragic love story. So no, the novel does not work. Sendker has a compelling story in here. But in an attempt to dramatize it even more, he completely fucks it up.

Tenth of December – George Saunders (2013)

This is the best thing I’ve read this year. I feel like I’ve discovered a new favorite author with this collection. I’ve never felt so in line with the sensibilities of a book. The stories here are mostly comedies, all of which are very dark.

The first story, “Victory Lap,” is such a feat. We get internal monologues from three perspectives. A 15-year old girl who fantasizes about different suitors appearing to court her. During this narrative, she looks out the window and sees her weird neighbor running home from cross country. We shift to his perspective. He is hyper-sheltered from his parents. His objective is to place a geode in the backyard garden so he can earn chore points and get a scoop of yogurt with raisins. As he goes to do this task he sees a man approaching his neighbor’s house. We then move into the man’s perspective. He is here to kidnap and rape the girl. He’s stolen his friend’s van to do it. As he kidnaps her, the three perspectives come together. The girl and the man are in a struggle. The hyper-sheltered kid is frozen, knowing his parents would kill him if he did anything but look away. But he breaks free, running with the geode and smashing the man and his car. It’s so dark and so unbelievably funny. Besides the absolute genius in how Saunders structures the story, it is how much empathy he has for each of the character’s perspectives. He gives them realistic hopes and aspirations. Even if they’re totally depraved. For how dark the story is, you really come away thinking what a humanist Saunders appears to be.

I would argue this is no more clear than in “Escape from Spiderhead.” This story is definitely much less funny than some of the others. It does something maybe even more challenging. It is so dark and yet probably shows more humanity than 99% of other stories. We meet our narrator who, through a dystopian, future prison is subject to drug testing. One of the drugs, in particular, makes you fall in love at such high intensity. In each situation, he and his counterpart have sex three times and talk as if they’ve known each other all their lives. We realize as the experiment goes on, that the prisoners will have to be subject to the opposite sensation. A drug so thoroughly depressing that it kills one of the prisoners. At the end of the story, our narrator uses this drug to kill himself in order to stop another prisoner from experiencing it. It shows such humanity, from a killer no less, in the face of utter darkness.

The best story in the collection, and arguably the best story I have ever read is “The Semplica Girl Diaries.” There were times reading this story in which I couldn’t even look at the page from laughing so hard. The conceit of the story is that it is a series of journal entries, one page, every day, from a downtrodden, ordinary man. The outset is hilarious. He drops articles frequently. It feels like a precursor to the way Drumpf addresses the nation on twitter. He also addresses us as “future reader” and asks us if we’re still familiar with such mundane things as credit cards. It feels like such a joke. But there’s a twist. It actually reminded me of how the comedy in “I Think You Should Leave” is structured. We are laughing from the outset, but we don’t even know what the joke is yet. The twist here is that this man is not writing from our world but an actual dystopia. One in which, as a display of wealth, families hang up living immigrant girls as garden decorations. The man, in another absurdly comical twist, wins the lottery and finally has a chance to buy these symbols of wealth. It wrestles with the complexities of wealth and morality, while also being obscenely dark and funny.

I feel like I could highlight every story in the collection. I would definitely like to shout out “Puppy” as well as “My Chivalric Fiasco.” What really cemented this book for me is the title story. There’s not a whole lot to say except that it’s funny, beautiful, and so sad. Saunders is so good at writing from the perspective of the down-trodden and yet never really makes fun of them. If he does have some laughs at their expense, it’s because we ultimately sympathize with them. It’s such powerful and lively writing. I’m sure it’ll stick with me.

November

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy – Douglas Adams (1979)

I read this on the recommendation of Bryce. When I had mentioned Tenth of December, he said he hadn’t read a really funny book in a while and wanted to re-read this. This book is really funny. It’s extraordinarily absurd. The level of absurdity actually threw me off a bit. This book is so unconcerned with traditional mechanics, like plot, I was a bit lost in it. Because my book contains a making of the feature section in the back, I didn’t even realize I was near the end until it was over. Looking back on it, I’m beginning to appreciate the novel as a whole. It’s a small, clever story. One that really only comes together when you take it in as a whole. I wouldn’t say this is one of my favorites. Especially not in the way it is for a lot of people. It was fourth in the BBC’s Big Read! Still, Adams’ narration is really funny. The book is smart and clever. I think I would have appreciated it more if not for its legacy.

The Old Man and The Sea – Ernest Hemingway (1951)

I don’t have a lot to say. Will my brevity be as profound as Hemingway’s prose? Hopefully. This story is wonderful. It’s completely engaging. It’s thoughtful and meditative. I’m so glad I read it. The thing that shines most is Hemingway’s writing. His language is crisp and clear. He writes 127 pages without breaks. It’s one continuous story. It’s a real feat as a writer.